Australia’s housing market has been the topic of much discussion, and for good reason. With population growth on the rise and the demand for new homes increasing, it’s important to understand the current situation and what the future holds. This article delves into the data to provide a comprehensive overview of the challenges and imbalances within the housing sector.

Annual population growth in Australia is anticipated to increase. In response to this, the need for new homes has risen as well. Over the past five years, the demand for new dwellings averaged around 147,000 per annum. However, over the next half-decade, this underlying demand is likely to reach 227,000 each year, representing an 80,000 increase or a 54% boost. With these numbers in mind, Australia must essentially build the equivalent of a Canberra or Newcastle each year, with the 80,000 increase behaving like constructing another Hobart annually.

Moreover, the demand for new housing builds during the 2022/23 financial year is projected to be 273,750, which is akin to building another Gold Coast. These are undoubtedly big numbers, but it’s crucial to note the methodology behind calculating new housing demand. Based on the number of adults per dwelling (1.92 for Australia) and accounting for an average of 0.58 children per household, it’s important to remove children from the equation since they typically live with adults.

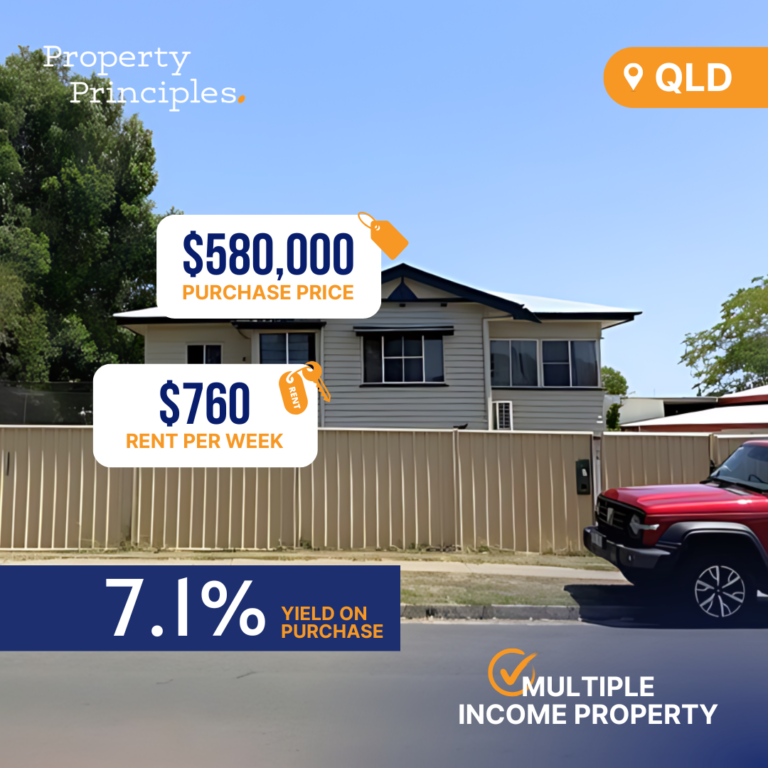

When it comes to dwelling commencements and measuring supply against demand, there have been only 171,500 commencements during the 2022/23 period. This reveals that the new housing market is undersupplied by approximately 102,000 dwellings or 38%. All states and territories are experiencing undersupply this year, although some, like New South Wales, Victoria, the Northern Territory, South Australia, and the ACT have had adequate new builds over the past five years. Meanwhile, Queensland, Western Australia, and Tasmania remain undersupplied.

This situation can be partly attributed to the dip in housing demand during the 2020/21 period (due to Covid-related immigration restrictions), with annual population growth plummeting to just 32,790 and new housing demand sitting around 18,000. However, new housing commencements totaled 213,700, driven by initiatives like HomeBuilder and record-low interest rates. Interestingly, about 15% of these new housing starts (~33,000 dwellings) have yet to be completed, which can be linked to Australia’s building industry struggles and state government building programs, particularly in Queensland ahead of the 2032 Olympics.

Moreover, approximately 16% (34,000) of the new housing starts during the 2022 financial year have not yet been completed. This means there are almost 70,000 new dwellings in the Australian new building pipeline. Assuming these dwellings are eventually delivered, they will help alleviate housing supply issues; however, it’s worth noting that these 70,000 new dwellings only represent 25% of the 2023 demand.

It’s also essential to consider that a significant portion of new housing in New South Wales and Victoria is purchased by offshore interests. It’s estimated that as much as 30% of this stock is locked up and only occasionally used, if at all. This is a problem that needs to be addressed as Australia grapples with its housing demand and supply imbalance.

The takeaway is that while there is progress being made, there is still a long road ahead to ensure that the Australian housing market can adequately meet the needs of its growing population. It’s essential to continue monitoring these trends and working towards solutions to ensure that everyone has access to a suitable and affordable place to call home.